Many of us are familiar with the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like Advil, Motrin and Aspirin. They’re among the most versatile and arguably well-loved drugs in our medicine cabinets. They offer good pain control, reduce inflammation, and can treat fever effectively. We give NSAIDs to infants, continue them in adulthood for the aches and pains of modern life, and take them regularly, often at prescription-level dosages, in our later years for the treatment of chronic conditions like osteoarthritis. An astonishing 17 million Americans use NSAIDs on a daily basis, and this number is expected to keep growing as the population ages.

Surprisingly, while drugs like ASA (aspirin), naproxen and ibuprofen don’t require a prescription, they have a long list of serious side effects. Not only do they cause stomach ulcers and bleeding by damaging the gastrointestinal mucosa, there are cardiovascular risks, too. It was the arrival (and departure) of the drugs Bextra and Vioxx that led to a much better understanding of the potential for NSAIDS to cause cardiovascular toxicity. It is now clear that these effects are not limited to the “COX-2” drugs: All NSAIDs seem capable of raising the risk of hearts attacks and strokes.

Now a new meta-analysis published in The BMJ suggests that the risks of heart attacks and strokes could be raised after only one week of taking an anti-inflammatory drug regularly. How does this change how we should use them?

NSAIDs 101

NSAIDs all work in the same way, blocking the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, responsible for the production of prostaglandin messenger substances that cause pain, inflammation and fever. This mechanism of action is also responsible for the extensive list of side effects, a consequence of COX enzymes being distributed throughout the body. NSAIDs cause a startling amount of harm. They have been linked to about 30% of drug-related hospital admissions, and it’s estimated that 12,000-16,000 Americans die annually as a result of gastrointestinal bleeding caused by NSAIDs. The risks of gastrointestinal toxicity are significantly increased in the elderly, in those on high doses of NSAIDs, and when combined with other drugs (e.g., steroids) that suppress normal stomach protection. Fortunately these side effects can be prevented with drugs like proton pump inhibitors.

The other well-known side effect is cardiovascular disease, and the evidence is now quite clear that NSAIDs increase the risks of heart attacks and strokes.

There are two main subtypes of COX enzymes (conveniently, COX-1 and COX-2), and the affinity of a particular NSAID for the different COX enzymes has been thought to be the main factor influencing the degree of cardiovascular risk. The COX-2 inhibitors like Vioxx had fewer effects on COX-1 in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing side effects, but effects on COX-2 are more closely linked with increases in events like heart attacks and strokes. These effects may be a consequence of interference with the beneficial effects of concurrent low dose ASA, direct negative cardiovascular effects, and/or worsening of fluid balance, leading to heart failure. What hasn’t been clear is how quickly a user of NSAIDs may face an increased risk of a harmful cardiovascular event .This new paper starts answering that question.

Despite the headlines you may have seen, this analysis from Bally and colleagues is a systematic review, and not a new clinical trial. Published in The BMJ, it’s entitled “Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data.” The fact this uses individual patient data (IPD) is notable. Most meta-analyses pool the results of trials. IPD meta-analyses pool and analyze the raw patient data from different trials. If that sounds cumbersome, that’s because it is. Cochrane considers IPD meta-analysis the “gold standard” of systematic review methods.

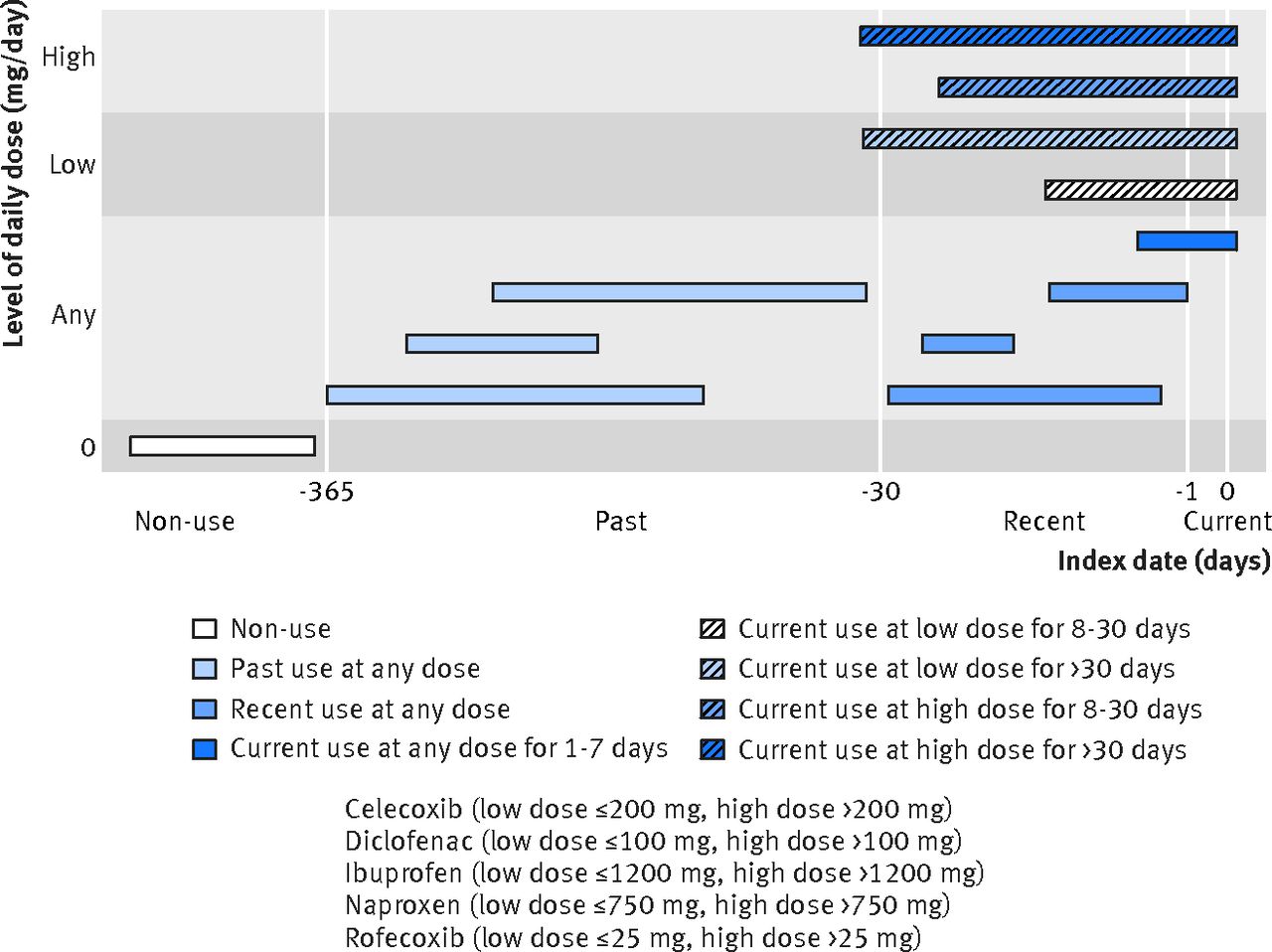

The researchers set out to examine the characteristics and time course of heart attacks (myocardial infarction) with the use of NSAIDs. Datasets were searched for observational studies of large healthcare databases that compared the risk of myocardial infarction in NSAID users and non-users, and that allowed for an analysis by time window. They also had to provide adequate detail about the NSAIDs consumed. Given the restrictive criteria, only a small number of possible trials could be used. The researchers eventually used data sets from Quebec, Saskatchewan, Finland, and the United Kingdom, totaling over 61,000 patients who had heart attacks. The NSAIDs of interest were celecoxib, the three commonly used NSAIDs, (diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen), and rofecoxib (Vioxx). With all this data they created categories of use that sorted patients according to when they took an NSAID, what their dose was, and how long they took it. The index date was the date of hospital admission for a heart attack:

With these types of studies there’s a huge potential for confounders, or factors that influence the observed relationship. The list of possible confounders the researchers generated was extensive (and I won’t detail it here, plus other aspects of the review, in the interest of space). For the analysis, they studied the results of the four trials, but also the pooled patient data. They used a Bayesian framework to make probability statements about the risks in different time periods.

The results: Significant elevations in risk

In total there were 61,460 cases and 385,303 controls. Between the four trials included, the populations differed significantly. This study found that there was a relative risk increase of 20-50% overall, with what appears to be a 75% increase in risk for ibuprofen and naproxen, and over a 100% risk increase for rofecoxib (Vioxx). The risk of heart attack appears to increase almost immediately (and decrease over time after the last use of an NSAID). There was also a dose effect observed, with higher NSAID doses appearing to correlate with greater risk. Interestingly, risk didn’t continue to increase beyond a month of therapy. That is, there appears to be greater risk of heart attack if an NSAID is used beyond one month. There were some small but modest differences between the NSAIDs studied. Notably, naproxen appears equally harmful to other NSAIDs, while celecoxib (Celebrex) appears no more harmful than the other NSAIDs.

There have already been some criticisms raised in the rapid responses, which seems to focus on the apparently immediate onset of risk with NSAIDs, which some feel may be related to reverse causation, in that these patients may have been taking NSAIDs for the pain of a (subsequently-diagnosed) heart attack. It should also be noted that non-prescription use of NSAIDs is no considered in this paper, as that data was not available. Given the widespread use of non-prescription NSAIDs, it’s really not clear to what extent this may have influenced the findings.

Absolute versus relative risk: Beyond the headlines

While the risks found in this analysis appear to be real, it’s essential to recognize that these are relative risk increases, not absolute risk increases. If your underlying risk is low, then the incremental risk is low. This paper does not report absolute risks. The authors suggest using a risk calculator like the Framingham Risk Score to estimate the 10 year risk of coronary heart disease, and use that finding as a guide to place this research in context. They note:

Without use of NSAIDs, one could expect that the number of cases of acute myocardial infarction will be fewer than 1 case per year per 100 persons in those at low risk (less than or equal to 10% over 10 years), 1 to 2 cases per year per 100 persons in those at intermediate risk (10-20% over 10 years), and greater than 2 cases per year per 100 persons in those at high risk (>20% over 10 years).

Assuming an increase in the relative risk of acute MI of 20 to 50% across NSAID doses and durations studied in the IPD meta-analysis, the number of excess acute myocardial infarctions associated with use of common NSAIDs might range from fewer to 0.2 to 0.5 case per year per 100 persons in those at low coronary risk or < 0.2-0.5% annually (< 2 to 5 cases per 1,000 persons per year) up to 0.4 to 1 or more cases per year per 100 persons in those at high coronary risk or > 0.4 to 1% annually (> 4 to 10 cases per 1000 patients per year). Hence the absolute percentage increase of excess MIs due to NSAID exposure is likely to range from 0.2% to 1% annually.

Emphasis added.

Treating pain: Between a rock and a hard place?

It’s important to remember that this new paper doesn’t change what we’ve known for some time: If your baseline risk of a heart attack or stroke is low, then NSAIDs raise your risk only slightly. However, given the fact NSAIDs are taken so casually, the apparent rapid escalation of risk should concern anyone with a modest- to high-risk of a heart attack who might not normally have worried about several days of high-dose NSAID use (say, for an acute injury). What this analysis shows is that there’s an apparent rapid increase in risk.

Overall, these findings reinforce the fact that we lack safe and effective treatment options for chronic pain control. With the opioid epidemic killing thousands across North America, there’s more awareness than ever of the risks of using narcotic analgesics for acute or chronic pain. However, many patients with chronic pain may be older, or have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and shouldn’t be on NSAIDs. Given the modest and even questionable effectiveness of acetaminophen (Tylenol) for many types of chronic pain, there are few effective medical options remaining. I’ve written before about topical NSAIDs which appear to lack the toxicity of oral products. They may be a reasonable alternative for those that want to minimize their risk, or are seeking treatment alternatives.

Use with caution

With the populating aging, the need for effective treatment options for conditions of age, like osteoarthritis, will continue to grow. It’s now clear that indiscriminate use of opioids have been a public health disaster. What’s less obvious, but also causing substantial harms, are the NSAIDs. This well-done individual patient data systematic review provides useful data to health professionals and consumers alike: The risk of harm from taking an NSAID, even products like ibuprofen or naproxen, is low, but increases quickly with use. Regular usage of the NSAIDs studied, beyond a week or more, is associated with a modest (but real) increase in the risk of heart attack. NSAIDs provide good pain relief and can decrease inflammation. But they have the potential to cause significant harm, which increases with dose, duration of use, and the underlying risk. Use them if you need them, but only if you need to, at the lowest dose possible, and for the shortest duration possible.

Photo from flickr users Beau Lebens and Jonathan Cohen used under a CC license.